- Home

- Lesley Eames

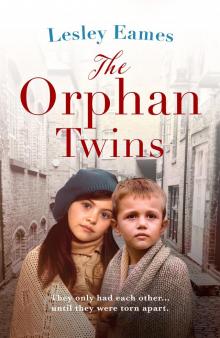

The Orphan Twins

The Orphan Twins Read online

Also by Lesley Eames

The Runaway Women in London

The Brighton Guest House Girls

The Orphan Twins

THE ORPHAN TWINS

Lesley Eames

AN IMPRINT OF HEAD OF ZEUS

www.ariafiction.com

First published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by Aria, an imprint of Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright © Lesley Eames, 2020

The moral right of Lesley Eames to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781788545747

Cover design © Cherie Chapman

Aria

c/o Head of Zeus

First Floor East

5–8 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

www.ariafiction.com

Contents

Welcome page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Become an Aria Addict

For my beautiful daughters, Olivia and Isobel, who bring joy to my world.

ONE

Bermondsey, London

January 1910

Lily entered the yard from the alley that ran behind the shabby little terraced house that was home. Seeing Gran at the kitchen window, she raised a hand in a wave only to realise that Gran was hunched over the sink in what looked very much like pain, her eyes screwed shut and her lips clamped tightly together.

Lily’s steps came to a halt as she was torn between rushing to darling Gran’s aid and allowing Gran her pride because Maggie Tomkins would hate to be caught out in what she was likely to consider weakness. Standing watching for a moment, Lily hoped Gran had simply stubbed her toe or received a minor burn from a hot iron. Despite that hope, the memory of Mum doubled up and coughing blood caused a chill to rise up Lily’s spine.

‘Cor, Lil! Dunno where it came from but it was a whopper!’ Artie burst into the yard behind her, having paused to inspect a caterpillar he’d noticed in the alley.

The noise roused Gran who looked up and straightened with a guilty air as though she’d been caught out in wrongdoing. Always hungry, Artie rushed into the kitchen for his dinner. Lily followed, but slowly. Thoughtfully.

‘Are you home for your dinners already?’ Gran said, wiping sweat from her forehead. ‘I wouldn’t have stood idle if I’d realised the time. But it’s hot in here with all this ironing and there’s only so much heat a body can take before she needs to catch her breath.’

She waved round the room at all the shirts she’d ironed. Two irons sat in the hearth warming up for the next lot.

Had she really only been catching her breath? Being a washerwoman was certainly back-breaking work. But Gran was pale instead of flushed and could easily have opened the door or window to let in a blast of freezing winter air if she’d needed to cool down.

Lily looked back at the shirts and wondered if there were actually fewer of them than normal. If Gran was ill, it stood to reason that she’d be unable to work as hard.

‘Let’s get some food inside you,’ Gran said.

‘I’ll fetch it,’ Lily offered quickly. ‘You put your feet up.’

‘Put my feet up when there’s work wants doing?’ Gran laughed, but Lily persisted.

‘Just for a minute or two. I’ve been sitting down at school all morning. I need to move around.’

‘Maybe I will sit down,’ Gran finally conceded. ‘But not for long.’

To Lily’s relief, Gran pulled out a chair that was tucked under the small kitchen table and sat. Lily moved to the cupboard where food was kept along with plates, cups and cutlery. Inside she found a loaf on a wooden board which she carried to the table together with a knife before returning to the cupboard in search of something to put on the bread.

Artie loved the meat paste that came in round white pots but it had been a long time since they’d had any of that. Sometimes there was cheese but not today. There was butter but not much of it so Lily reached for the jam pot instead. Gran had made the jam from the blackberries Lily and Artie had gathered from any stray bush they’d been able to find in the autumn months but the jar was already half-empty and there weren’t any more. Less work meant less money coming in, of course, and that meant emptier cupboards.

Gran had been ill only twice before as far as Lily could remember. The first time, they’d all had upset stomachs and spent the day dashing outside to the privy. Gran had blamed a piece of mutton she’d cooked in a stew. ‘I’ll give that butcher a piece of my mind,’ she’d threatened, and as soon as she was well enough she’d marched into his shop to tell him what had happened.

‘’Course that mutton was off,’ she’d insisted when he’d argued. ‘You must have let it sit in the window too long.’

‘I didn’t!’

Gran had simply crossed her arms and waited.

‘Look, I’m not saying you’re right,’ the butcher had finally said, looking round at his other customers as though fearing they might take themselves and their custom elsewhere. ‘But I can see you’re out of sorts so, just to show I’m a man who likes to help his customers, I’ll make you a gift of a nice string of sausages.’

‘I’ll take some bacon too,’ Gran told him. ‘And the same again next week.’

Gran was afraid of no one but there’d been no free sausages or bacon the second time she’d been ill because there’d been no one to blame for her bad chest. The only wonder was that her chest hadn’t been bad more often considering they lived in a house that spent its days filled with steam and its evenings with the steam turning to drips downs walls and windows. Sometimes the drips turned to ice.

Lily decided to say nothing of her suspicions for the moment, seeing as Gran obviously didn’t want to worry them. Lily didn’t want Artie worried either. But she’d watch Gran carefully from now on and help as much as she could.

She cut a thick slice of bread for Artie as he was always so hungry. ‘Gran?’

Lily invited.

‘I’ll have mine later.’

Would she, though? Probably not, if food were in short supply. Lily was tempted to go without eating too but Gran would know then that she’d given the game away about being unwell. Her pride would be hurt as Gran liked her grandchildren to be both well-fed and well-shod. No running around in bare feet in all weathers for them. Artie would realise something was wrong as well. Reluctantly Lily cut a slice of bread for herself but made it a thin one. She spread jam liberally on Artie’s slice but added little more than a dab to her own.

She picked her slice up quickly to hide the lack of jam but Artie had already noticed. ‘I’ve got more jam than you,’ he pointed out. He was a sweet boy who liked to be fair.

‘You’ve got more growing to do,’ Lily told him, hoping a little good-natured teasing would distract him from the jam before Gran noticed it too.

Artie pulled a face. It was a sore point with him that Lily should be just thirty minutes older yet a whole two inches taller. ‘You a girl and all,’ he often complained.

Lily took after their father and Gran, being straight and slender with the near-black hair and blue eyes common among people from the Irish homeland Gran had left as a child – though Gran’s hair was white all over now. Artie was more like their gentle mother – small and soft with honey-coloured eyes and toffee-coloured hair.

‘Just wait until we’re eleven,’ Artie said now. ‘I’ll catch you up and leave you behind.’

‘We’ll see,’ Lily said, smiling, and she was glad to see Artie tuck into his bread with every sign of having forgotten his extra jam. ‘School was good this morning,’ she said, changing the subject before he remembered it. ‘Miss Fielding said she was pleased with my handwriting.’

‘You always write a nice hand,’ Gran said.

‘Davie was sick in my class.’ Artie grinned.

Lily looked at Gran and they both rolled their eyes. Boys laughed at the oddest things. ‘Poor Davie,’ Gran said.

‘He said he felt better afterwards. I think he did it on purpose because Mr Simpson has new shoes and—’

‘I think we’ve heard enough of Davie,’ Gran said. ‘You’ll put us off our dinners.’

Talk of Davie’s indisposition hadn’t put Artie off his dinner. He crammed his bread into his mouth and ate it hungrily. Lily ate hers more slowly then lifted the kettle onto the fire to save the cost of lighting the gas on the stove. It was a rare day when there wasn’t a fire in the kitchen hearth. Gran boiled most of the washing water on the stove in the big copper but the fire was used for extra water as well as for heating the irons and drying the washing, especially at this time of year when it could hang on the lines in the yard all day and still come in damp.

Gran looked out of the window where sheets billowed on the washing line like sails. ‘I’d better fetch that lot in,’ she said, hands flat to the table as she levered herself out of her chair.

To Lily’s eyes it seemed to require more effort than usual. Lily waited until Gran was outside then got up to return the loaf and jam to the cupboard. With her back to Artie so he couldn’t see what she was doing, she reached for the old tea caddy in which Gran kept their money. It felt worryingly light.

Replacing it, Lily took out cups and a small jug of milk. The rest of the milk was kept in the front parlour where it was cooler. They used their tea leaves three times before they gave them to Harold Finnegan on Grace Street to use on his allotment in return for occasional vegetables or rhubarb. It was a day for new leaves but Lily used the old ones again. There wasn’t much life left in them but hopefully Gran wouldn’t notice the tea was weak.

‘Any buttons to sew back on?’ Lily asked, as Gran returned with her arms full of washing.

Gran’s sight wasn’t what it had once been so sewing was a job Lily took on gladly.

‘A few. There’s a fallen hem that needs mending too.’

Artie drank his tea then wandered back outside to see if any of his friends were playing in the alley. Lily set to work with the sewing, glancing in Gran’s direction occasionally and noting the lines that cut crevasses into the ageing face. Gran was definitely under the weather but everyone felt under the weather sometimes and usually they got well again.

Not always, though. Dad had dropped dead unexpectedly due to a sudden bleed on his brain. Within a year Ma had fallen ill. Tuberculosis, the doctor had called it, though everyone else had called it consumption. Arrangements had been made for her to go to a sanatorium at the seaside where the air was cleaner but she’d been taken off by pneumonia before she could get there.

The cold lick of dread was back in Lily’s stomach. ‘Why don’t I stay at home this afternoon and help with the laundry?’ she offered.

‘And miss school? You’ll have one of those inspectors down on me for keeping you away from your book learning.’

‘We aren’t doing book learning this afternoon.’ More was the pity because Lily loved it. ‘We’re doing sewing and you’ve taught me all I need to know about that.’

‘You’re a quick one, that’s for sure. Your dad always said so.’

Lily remembered overhearing Dad saying exactly that and adding, ‘I wish Artie were half as quick. It doesn’t seem fair that a girl should have more brains than a boy when it’s Artie who’ll have to put food on the table when he’s older.’

Gran had pointed out that, as a widow, she’d been putting food on her own table for years as did countless other woman.

‘I know,’ Dad had admitted. ‘But let’s hope Lily finds a decent man to make her life easier than ours. No one’s quicker at working out pounds, shillings and pence than Lil, and if she can work in one of those smart shops up West she might be in the way of meeting someone. But Artie…’

‘The boy’ll catch up. Lily’ll see to that.’

‘You’re right there.’

‘I just want Lily and Artie to be happy,’ Mum had said, and Lily had imagined both Dad and Gran smiling fondly because Mum had been a tender-hearted, domestic soul of neither education nor ambition.

She’d been perfectly content to stay at home and make a little money sewing for others though that sort of work paid only a fraction of a man’s wage. Lily understood that work like Pa’s job of loading and unloading ships down on the docks needed a man’s strength. But women’s work took a different sort of skill and it didn’t seem fair that it should pay so much less. After all, where would men be if their clothes fell apart for want of a timely stitch or if they had nothing hot to eat on a winter’s night?

To Lily’s way of thinking, people were like pieces of jigsaw puzzles. They came in different shapes and sizes but all of them were needed to make the puzzle complete.

Not that Dad had particularly enjoyed his job. ‘All that lifting, pulling and pushing wears a body out,’ he’d said another time. ‘But I didn’t have much schooling so I’m not fit for anything else. I’ve seen how schooling can raise some men up to better jobs so I hope you’ll pay attention to yours, Artie.’

‘I’ll try, Dad.’

Artie was no dunce but he had some silly boys in his class and, despite his good intentions, he wasn’t above being silly himself. Looking back, Lily sometimes wondered if Dad would be with them still if his work hadn’t put so much strain on his body. She didn’t want the same thing happening to Artie and, in any case, she wanted her brother to have a choice about how he made his living so she was glad to do what she could to help him.

Luckily, they had some wonderful books that Dad had bought for them from the second-hand shop. Dad hadn’t been much of a reader – he’d stumbled over long words – but he’d wanted Artie to read well and had known how much pleasure books gave to Lily too. On his last Christmas he’d come home with Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories and they’d had great fun imitating the animals in the stories. Dad had loved to laugh.

Lily finished Gran’s sewing then went into the alley to call Artie. ‘What?’ he asked, running up to her.

&nbs

p; ‘I thought you might do a few sums before we go back to school.’

Artie looked back at his pals longingly, but he was too nice-natured to argue. Back in the kitchen Lily fetched a scrap of paper from the box in which they kept old envelopes and anything else that had a spare bit of space for writing. She wrote out some simple sums to warm up his brain and, while he worked through them, picked up the three-legged wooden dolly, plunged it into a tub full of washing, and twisted it this way and that to stir the clothes and – hopefully – shift the dirt from them.

There didn’t appear to be much soap in the water today. Gran was never wasteful but she took pride in her work and didn’t usually skimp on soap, soda and starch. Was the lack of soap another sign that money was especially tight at the moment?

Coming in from the yard after putting some sheets through the mangle, Gran peered into the tub regretfully. ‘Better grate a few more flakes in,’ she said, not managing to hide her disappointment over the fact that they were needed.

Lily rubbed the block of soap against the grater to send a tiny cascade of flakes into the water then got back to work with the dolly. When Artie had finished the easy sums, she set him a harder one. ‘How much would it cost to feed a family of six for a month if they all have an egg for breakfast and eggs cost a penny each?’

‘Eggs for breakfast!’ Artie eyes lit up at the thought of it.

‘Pay attention to your lessons and maybe one day you can have eggs for breakfast,’ Lily said.

She waited for him to ask a vital question. ‘Which month, Lil?’ he finally said. ‘Some months have more days in them than others.’

Lily beamed. ‘Let’s say July.’

‘Thirty-one days, then.’

He sucked on the end of the pencil then worked out that six eggs a day for thirty-one days meant one hundred and eighty-six eggs. At one penny each the cost was fifteen shillings and sixpence.

‘All that money!’ Artie said.

‘More than many a man earns for a full day’s work,’ Gran pointed out, and Lily supposed it was more than Gran earned for several days’ work.

The Wartime Singers

The Wartime Singers The Runaway Women in London

The Runaway Women in London The Orphan Twins

The Orphan Twins The Silver Ladies of London

The Silver Ladies of London